Webscraping Real Estate Market Data

Using BeautifulSoup and Python to scrape real estate data from the web

At the beginning of every data science project the central question is: where do we get the data from? As is the case for many projects, the web provides us with tons of data which can be used- if one knows how to obtain it. This first post of our Real Estate Data Science Project series shows how to web scrape using the example of the Spanish real estate market.

This article proceeds as follows:

- Finding the right scraping strategy for the project

- Inspecting the HTML code and initial steps

- Scraping properties from each province

- Problems caused by website irregularities

- Conclusion

01 Finding the right scraping strategy for the project

Web scraping can be tiresome. That is because web scraping truly depends on how clean the html code underlying the website is. Every time there is an irregularity, the scraping will run into problems, resulting in the need to run the entire process again. Later in this blogpost several of these irregularities will be shown with their respective workarounds. Pragmatic solutions are critical. Web scrapping is truly the “dirty work” of data science. On the plus side, having this ability to create data out of nothing is essential and the basis for many data science projects. It also opens up a wealth of project options that otherwise would not be available if one had to rely solely on published data.

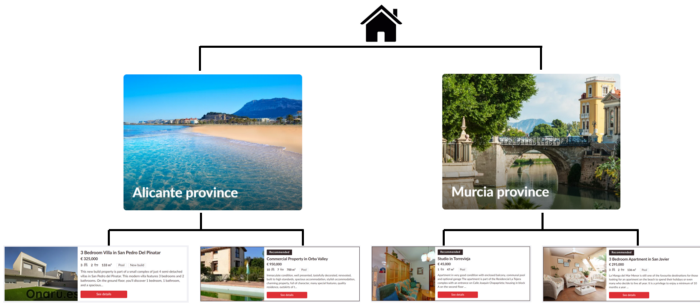

Given the oftentimes frustrating nature of web scraping, it is essential to automate as many steps in the scraping process as possible. As an example: the Real Estate observations which are scraped for this project are divided into different areas in Spain. That means in order to find and group every property for each area it is first necessary to find all the URLs associated with that individual area. This strategy of finding the hierarchical nature of the data on the website is visualized below. Here, two explanatory provinces from the website are shown, namely Alicante and Murcia. Clicking on these pictures on the website then leads to the available properties in each of those regions. The graphic below shows two properties for each.

The strategy of the scraping then starts with first finding all the links to each province and second to scrape all the relevant property information for each region. With this plan and understanding of the website structure in mind, we can proceed to looking at the website’s underlying HTML code.

02 Inspecting the HTML code and initial steps

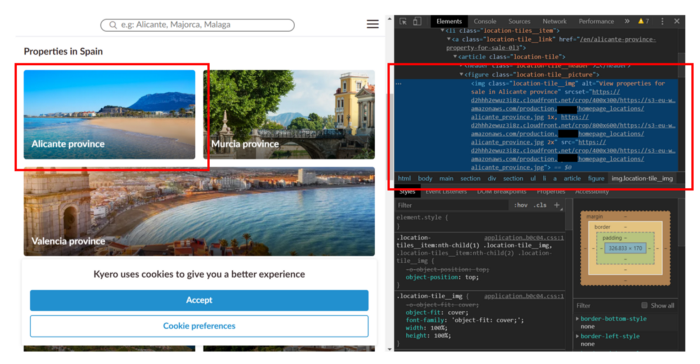

Opening the underlying HTML code of a website (Crtl+Shift+I) for the first time might be a scary experience. It is truly overwhelming how much information is stored behind the façade of a pretty looking website. The good news is that most of this information is not relevant- it’s all about finding the right point where to start. Our strategy outlined above tells us that the first thing we should find are the links to all provinces. Starting on the home page of the website, the first thing we do is to right click on (for example) the picture of “Alicante Province”.

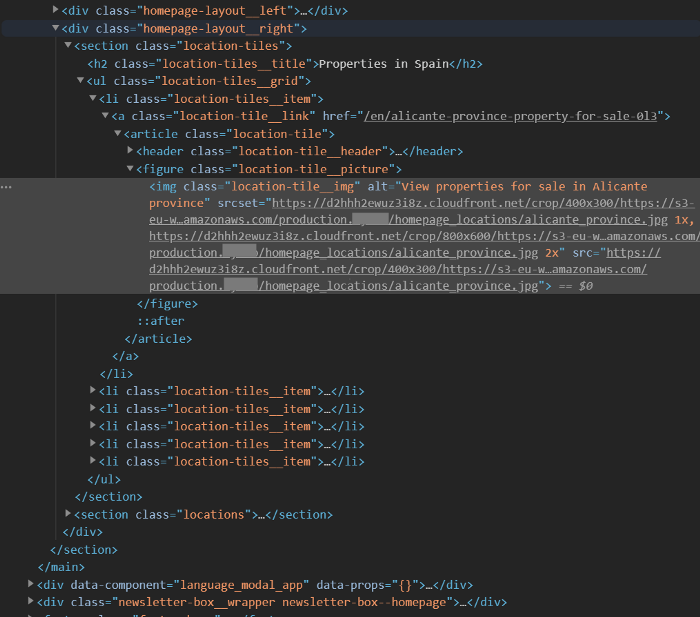

What is seen on the right side is the HTML code of the site. When we right clicked on the picture of Alicante, the HTML code of this picture gets highlighted in blue. We suspect that the link of the estate of Alicante are not too far from where the picture is embedded. Let us take a closer look at the HTML code:

As in the picture before that, we can see the highlighted (in grey this time) HTML code of where the picture is embedded. Also visible right above we find the URL of the properties for Alicante province. This information now has to be extracted. We want to repeat this process for all provinces on this website. To do so, it is important to see how the link is stored within the HTML code. Namely, it says:

<a class=”location-tile__link” href=”https://www.XXXX.com/en/alicante-province-property-for-sale-0l3”>

# Packages needed for scraping and extracting

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import re

# The website link

url = "https://www.XXXX.com/"

# Making the request look like a normal browser

headers = {'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/56.0.2924.76 Safari/537.36'}

# Requesting the sites content

page = requests.get(url,headers=headers)

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, "html.parser")

# Getting the relevant links

links_html = soup.find_all('a', class_='locations-list__link')

# Turning the soup into a list of strings

links_v1 = [str(x) for x in links_html]

# Extracting the relevant links for all regions

pattern = 'href="(.*)">'

links_v2 = [re.search(pattern, x).group(1) for x in links_v1]

What is happening here is that HTML of the URL specified is requested and saved. The header command disguises our request to make it look like a normal browser request of the website. Then the entirety of the HTML code is saved in the soup variable. Now the relevant part of how the links are stored within the HTML code kicks in. The first argument of the find_all command takes the tag name. The tag name is the first letter in the HTML code before the start of the object class. For this class, it is the letter a in the beginning of the code. The second part specifies what kind of class we are looking for here. This information was also already available to us within the HTML snippet. Afterwards we change the format into a string for easier usage later. Finally, we remove problematic substrings like “href=” in order to obtain the raw links. The output of that code looks like this:

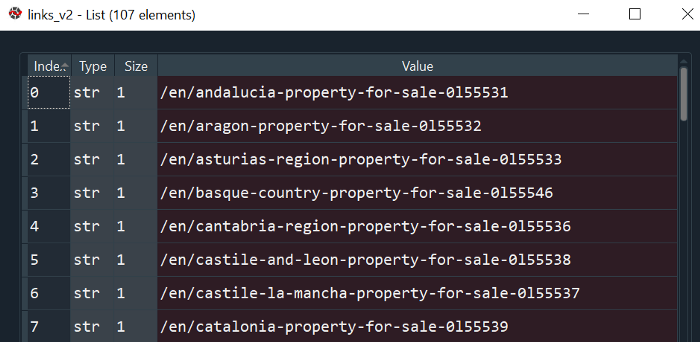

These links now open up the possibility to scrape properties from over 107 different provinces in Spain. One can only imagine how long that would have taken if done manually.

03 Scraping properties from each province

The next step after obtaining all provinces is to scrape the individual estate data from each province individually and loop over all provinces individually. The first step, as always, is to inspect the website.

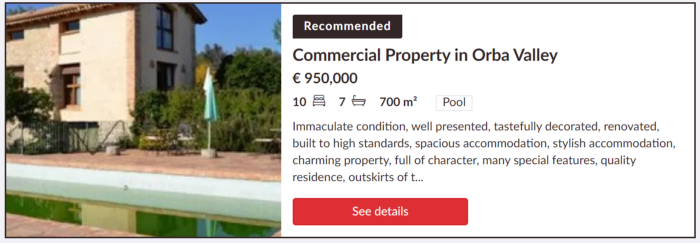

The picture above shows an example of what kind of information a property is providing. We are interested in extracting almost every detail provided. We want know for example how expensive the property is, how many bedrooms it has, number of bathrooms, square meters of living space has and whether it has a pool. All this information must be available in the HTML code if it is written on the website. After some deeper digging through the website’s code, we find following:

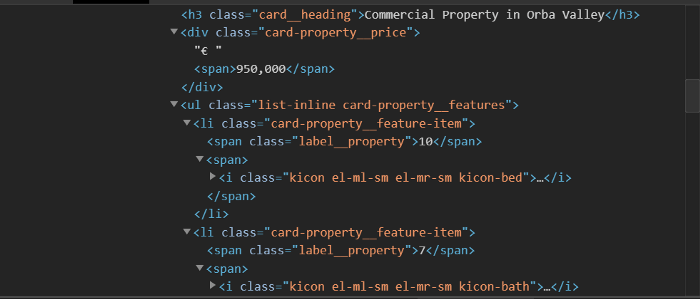

We can see that the information about the property price is nicely saved under the class card-property__price. The information about the bedroom and bathrooms is a bit trickier to find. Both of them are saved under the header “card-property__feature-item”. That does not make it very easy to distinguish bed and bathrooms. What is helping us here is the little icon the website is providing next to the number of each room. Namely, the little icon placed next to the number shows up with a distinct name in the HTML code, which reveals whether it is a bed or bathroom.

Bedroom: “kicon el-ml-sm el-mr-sm kicon bed”

Bathroom: “kicon el-ml-sm el-mr-sm kicon-bath”

The next question would then be how to best extract all this information in a neat and concise way. This problem is a bit more difficult than the extraction of links done earlier since the information is hidden further down within the HTML code. Furthermore, the information is not saved as the type “class”. This makes the find_all command a bit more difficult to apply. The workaround is to save the entirety of the HTML code as a string and use the regular expression package to scan the text. In order to see how that would look in code, the following snippet shows how the bathroom information is extracted. The variable “relevant_list” represents the HTML string of an estate.

# Specifying the pattern which incorporates the prices

pattern = '">(.*?)</span><span><i class="kicon el-ml-sm el-mr-sm kicon-bath">'

# Extracting the price information

bathroom_v1 = [re.search(pattern, x).group(1) for x in relevant_list]

# Taking the last part of each string since that contains the number

bathroom_v2 = [int(x.split(">")[-1]) for x in bathroom_v1]

To further explain the code shown in this snippet: the idea is to extract the number of bathrooms by finding the number in between a certain string combination. As we can see in the HTML, the integer of how many bathrooms an estate has is specified after an “>” sign and directly in front of the

</span><span><i class=”kicon el-ml-sm el-mr-sm kicon-bath”>

part. Once the bedroom information is located and extracted from the regular expressions search operator, it is saved in a list. This very same procedure is also applied to the number of bedrooms, the square meters of the property and whether it has access to a pool. Additionally, the small excerpt of the description text which every ad provides is extracted in order to apply Natural Language Processing algorithms to extract further features.

04 Problem caused by website irregularities

As with every web scraping project, the biggest cause of code adjustments and the need to re-run the code is the occurrence of irregularities. Glancing at a page of listings, an example can be quickly found

This property provides information about square meters, where it is located, and even has some nice advertisement text, but does not provide any information about bedrooms or bathrooms. This property is not useful as a datapoint since it lacks the information we would like to feed into our model. The extraction code provided earlier would run into a problem and break when it comes across this property. It would try to look for the occurrence of the bed and bathroom strings, which do not appear. This will result in an error and a necessary adjustment of the code. This problem is solved in the following way: Every property ad is first checked for the existence of all required strings. If all required strings do not exist, that property is eliminated and no further scraping actions are taken on the property. To do this, after each property’s full HTML code is separately stored, and advertisement text is separated from the other information. This text is then run through a test function which checks for the existence of substrings like “bed”, “bath” and “m²” within the HTML code. This works since these keywords only show up if the little icons denoting “bed”, “bath” or “m²” are also available. In the property shown above, these keywords would not exist since the little icons are not present. This property would then be eliminated during this test step.

05 Conclusion

Web scraping is a powerful tool and does not require very complicated coding. It does however require patience and creativity to work around irregularities. In the end our code was able to scrape 42,367 estates from the entire website. This should be enough not only for interesting analysis of the market, but also to train machine learning algorithm